An Introduction to the Young Hegelians

The times were dangerous. Almost all of the writings of the Young Hegelians were considered subversive. Even biblical scholarship was viewed as threatening when orthodox religious beliefs were considered essential to state security. One often hears jokes about how Marx wrote about money but was unable to make any himself. But this was a problem for all the Young Hegelians. Their writings led to persecution by the political, religious and academic authorities. They were dismissed from jobs, prohibited from teaching, jailed and exiled. When they moved from academic jobs to journalism their writings were censored, banned and their papers shut down. It was a precarious existence and this was reflected in the style of their writing.

They were responding to events and to each other. They were trying to remake the world which forever seemed on the verge of another revolution. The next one always promising to get it right, or at least better than the last one. The period was know as the Vormärz, literally “Before March” and refers to the time before the Vienna uprising of March 1848 that started a series of revolts and uprisings throughout Europe. The failure of the 1848 revolutions brought and end to an optimistic era that began with the July Revolution of 1830 in France. As a result of the turbulent times, their writing was done in a hurry. Sometimes they were on the run, but there was also urgency to what they were doing. Karl Löwith, in his From Hegel to Nietzsche, described them as “manifestos, programs, and theses, but never anything whole, important in itself” and that “in spite of their inflammatory tone, they leave an impression of insipidity.” This was a time to act and react; there was no time for careful scholarship.

This style is reflected in the enthusiastic young Feuerbach’s Letter To Hegel, 22 November 1828, the earliest of the Young Hegelian’s writings and can still to be seen two decades later in the Communist Manifesto of 1848, perhaps their final statement published as the revolutions broke out.

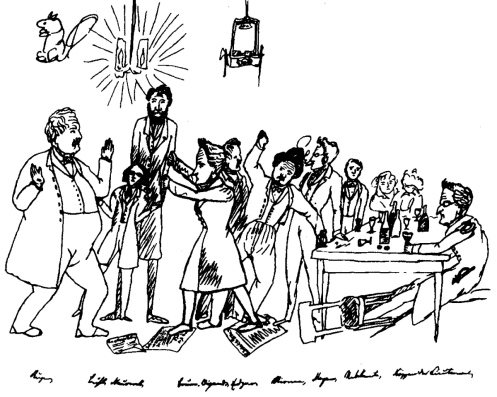

Despite their sometimes-heated philosophical confrontations it was a very congenial group. The went to each others weddings, loaned each other money (when they had some), visited each other in exile, wrote for each others journals and newspapers and collaborated on writing projects. In fact, there was so much collaboration that it is often hard to tell who—and how many—wrote a given text. This was complicated by the fact that may of their writings have to be published anonymously or under pseudonyms.

The Four Phases

The writings of the Hegelians fall into roughly four periods. In the first those known as the “Old Hegelians” or later the “Right Hegelians” collected, published and proselytized about the writings and lectures of Hegel. They were important for codifying and preserving the legacy of Hegel but they did not advance his philosophy so their impact was limited and their writings, beyond the collections of Hegel’s lectures, are rarely read and have not been translated.

The second phase was primarily interested in Hegel’s Lectures on the Philosophy of Religion. It began with David Friedrich Strauss’s The Life of Jesus Critically Examined, an 800 page scholarly work on the Gospels and an unlikely book that took the world by storm. The third phase moved beyond religious and theological issues to more practical issues of politics, economics and social life. The fourth and final phase is dominated by Max Stirner’s book The Ego and His Own and the critical reaction and debate that followed.

The Readings are as follows:

Introduction

1828 Feuerbach-Letter To Hegel, 22 November 1828 https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/feuerbach/

I. Old Hegelians (late 1820’s to 1835)

II. Religious Issues (1835 to early 1840’s)

1835 David Friedrich Strauss–The Life of Jesus Critically Examined

Preface to the First German Edition (pages 3-5)

http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/strauss/preface1.html

1. Inevitable Rise of Different Modes of Explaining Sacred Histories (pages 11-12)

12. Opposition to the Mythical View of the Gospel History (pages 43-47)

http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/strauss/introduction.html

140. Debates Concerning the Reality of the Death and Resurrection of Jesus (pages 842-853)

http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/strauss/ch3-4.html

1842 Max Stirner-“Art and Religion”

https://archive.org/details/al_Max_Stirner_Art_and_Religion_a4

III. The Pivotal Year of 1841

1841 Feuerbach-The Essence of Christianity, 1841

IV. Political & Social Issues (1843-45)

1843 Moses Hess-The Philosophy of the Act, 1843

https://www.marxists.org/archive/hess/1843/philosophy-deed/index.htm

1843 Marx/Engels-Letter to Arnold Ruge, Sept 1843

https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1843/letters/43_09.htm

Introduction to A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right

https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1843/critique-hpr/intro.htm

1843 Feuerbach–Principles of the Philosophy of the Future-Part III: Principles of the New Philosophy

https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/feuerbach/works/future/future2.htm

1845 Marx-Theses on Feuerbach Spring 1845

https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1845/theses/theses.htm

V. Stirner & His Critics (1845-1848)

1843 Max Stirner-“The False Principle of our Education”

https://archive.org/details/al_Max_Stirner_The_False_Principle_of_Our_Education_a4

1844 Max Stirner-The Ego and His Own 1844

Read three selections: 1) Part First: I. A Human Life, 2) Part Second: I. Ownness, 3) Part Second: III. The Unique One

https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/max-stirner-the-ego-and-his-own